Blog

Atom feed is here.

Here is the commit log from this last week of work.

2025-12-08

feat: add array and slice-generation macro and test for it

What happened?! The time has come to switch off of "C++". Even my beloved dialect of C++-that-is-actually-mostly-C leaves me with lots of work to do to create a language I'm happy to use, before I can get back to the problem at hand of developing a game.

As I refreshed my memory on search algorithms and studied pathfinding algorithms I was not familiar with, I realized I'd benefit from some more sophisticated data structures. As you can see from the commit above, I started to implement such data structures. I had three options. The first was to just use containers from C++'s standard library. I really didn't want to go this route for reasons I won't elaborate on here; suffice to say that I don't plan on depending more on C++ features in general. The second was implmenting my own code generator, like spec'ing out code with variables that a (hand-written?) templating tool would replace with values like type information, running this as a pre-build step, and then including the generated code in compilation. Again, more work, essentially somewhat re-implementing C++'s template features and also portions of what the third option was: preprocessor macros.

I opted for the third approach since, in theory, it is write-once-test-a-bunch-use-without-too-much-care-afterward. The natural place for this work was in the small standard library I was growing. I did prove out that I could generate a satisfying array type and a corresponding slice type. But honestly the thought of repeating that for a queue, a priority queue, a dynamic array, a hash map, etc. dissuaded me from continuing. Not only would I need to take a lot of care to avoid bugs and write a bunch of tests, I'd also need to get into the weeds about which implementation of which data structure was most optimal (or at least good enough), etc. And I just can't be bothered right now.

Coincidentally, I came across a podcast interviewing Jon Blow (this one? I don't quite remember unfortuantely), asking about why he was creating Jai and what hope he thought he had of creating a relevant C++ competitor or even replacement. I have been spending a lot of time thinking about whether to go all-in on Jai, weighing the tradeoffs of an actually-sane language but one developed and maintained by only a very small number of people (albeit with a big flagship project proving that the language is ready for production projects) and an industry-standard language backed by tools with massive user bases and a much larger number of contributors. Jon's answer was very convincing. In short, he said that we as a species have not used the same programming language forever. Even Big Industry switches languages over time. So if we accept that we are not going to use some particular language forever, then we don't have worry about asking ourselves whether we can compete with things like C++. Instead, we have to ask ourselves, when we do have a new language that we gravitate toward, which one will it be? Jai is Jon's language in this regard.

The last time I used Jai seriously was one year ago, last winter. Back then I

wrote essentially what I have now in "C++" and SDL (load tilemaps and sprites,

paint a level and a character, move the character around in a 2D world) but in

Jai and its built-in windowing abstraction called "Simp." So I spent a couple

days brushing up on the language and learning about what had changed since when

I last used it. After refreshing, I gave a Big Think over whether or not to use

Simp again for my project. I decided against it and chose to stay with SDL. So

I started exploring Jai's bindings generator tool that is often used to generate

Jai bindings to useful C and C++ utilities people want in their Jai projects.

At the time of this writing, there is an

open-source repo that uses the

bindings generator to create SDL3 bindings for Windows, macOS, and Linux. I

forked it and modified it a little to support my own workflow. Instead of the

current open-source behavior which wants a system-installed SDL3 library at

least for the Linux use case, I compile SDL3 from scratch for my project and so

want to point the bindings generator at that library at generation time. I got

it working in the end but suspect I was holding the tool wrong because there

was some non-obvious behavior such as transforming things like

../../build/libSDL3.so to __/__/build/libSDL3.so which broke library

loading at runtime untils I made some manual tweaks to the generator and also

stuffed a library in my source code instead of just in the build/ folder. So

despite it working, I wondered if there was an easier way overall.

Again coincidentally I came across some videos on YouTube about using Odin for game development. I've known of Odin for years but have never gotten into it. Odin does provide SDL3 bindings out of the box. Although not shown in the commit log at the beginning of this post, I've started down the Odin path, first to see if I enjoy the language enough to keep using it and second to see if it's any easier (by my taste) to achieve what I'm trying to do with Odin than it has been with Jai.

Currently I am opening a window via SDL3, painting the window the same gray background color I was using in my previous C-like implementation, and reacting to window-close events. The magic to work with my compiled SDL libraries is simply:

-

build SDL3 and emit libraries in

./build -

build my Odin project as follows

odin build src/ \ -extra-linker-flags:"-L./build" \ -out:"./build/game" \ -show-timings

Now, I am working on porting all my other code from "C++" to Odin. It's annoying, but it's best to pay this language-and-tooling cost up front in the project and have a consistent set of tools I enjoy using for the life of the project, which will likely be years.

So far, I think Jai is simpler than Odin, both in syntax and in its concepts. There are very many similarities in the language behavior and syntax. I cannot tell who inspired whom, presumably Jon-->Bill? Regardless, Odin hasn't been hard to pick up. The thing I spend the most time on is figuring out which types I should replace C-style buffers and arrays with in Odin. I'm only a couple days in, so maybe this is obvious and simple, but I'm just not there yet, have been playing more with SDL3 and doing a lot of reading about Odin to get a sense for its capabilities and staying power.

I did find one thing amusing, that there will be an upcoming change, part of which is explicitly passing an allocator into some functions (ref). I am already doing this everywhere in C, so no big deal. Jai passes a context to every Jai call that provides things such as an allocator so that callers can easily swap out the allocator used by third-party code, unless the library author explicitly chooses to ignore the requested allocator. I think Odin has something similar.

Next week I hope to have at least my previous game implementation but this time in Odin, if I don't decide to switch off of it.

Now that I'm doing my own thing, I've got more time on my hands to explore interesting posts, videos, books, etc. I've also resolved to put more of my thoughts here in this blog instead of on a variety of disparate networks.

A few days ago I came across a fellow by the name of Sylvan Franklin. I identify a lot with what his recent journey appears to be, but that story is for another time.

This post is prompted by The Addiction that hides in plain slight. In this post, I'll casually mix the target I am writing to.

One point Sylvan brings up is that many of us may have an addiction to information. I certainly do. I noticed this a few months ago, when I realized I would hesitate to start house chores or cooking until I found something interesting to listen to on my Bluetooth headphones.

One day, on a podcast I don't remember, I heard someone ask the rhetorical question, "how much information is enough?" The context implied the full question was, "how much information is enough to equip you to do what you think you need to do?"

I opened that question up more and realized the next implication, that I didn't actually have an agenda with any of that information. I didn't want to do anything with what I was "learning." In fact I told myself I was learning, but in reality I just wanted to be entertained. Learning is evidenced by a change in behavior, but I wasn't changing much. The gotcha was that every now and then I would consume something that resonated deeply with me--made me feel understood--or did change the way I thought and lived. What I became addicted to was the next revelation. But there is no promise of when or where this will come, much like there is no promise of when you may see something actually transformative while doomscrolling, be it a social media feed or a collection of proverbs.

In the end, I was just saturating my brain, hardly giving anything enough time and thought to personalize it.

You can tell when you've personalized something when you can communicate it to others without referencing anyone or anything else, that is, by appealing to personal experience and not authority, without saying, "the Senior Architect said...," or, "The Meditations say..." Now, let us not plaigarize, and if you want to cite the source, that's fine, but you haven't personalized something if you appeal to the source. One of the things I appreciate in Sylvan's recent videos I've seen is his self-awareness about his journey being personal.

"what I have to do is, do the hard work of coding everyday, or working on the math everyday, or reading philosophers everyday and thinking about them"

You already know the path forward! But perhaps you are not convinced yet. I'll elaborate below, but in the end, only you can convince yourself.

"What got you out of information consumption? I'm looking for the One Trick (tm)."

If you only look externally, you will be searching unsatisfied forever. As you say, it's like climbing a mountain. Looking externally has its benefits, but ultimately you will see others' techniques that worked for them. The catch is that the mountain you climb is your mountain. You can see their mountains from your mountain, or sometimes at least imagine their mountains. Your terrain might look like their terrain at times, but ultimately it is not their terrain.

The trick is to know who you are and where you are going. Knowing this in itself is a journey, and unless you concern yourself with cosmology, is perhaps the journey.

Who you are means understanding yourself--your nature, your past, your desires, etc. Consuming information externally is useful for bootstrapping your search. For example, Zen--as you've also discovered--and the "noting" meditation technique worked well for me, and understanding this and that about behavioral psychology was also useful. The trigger to look inward was looking outward for answers to questions about myself until I realized I am the only one who knows me. That, and after having asked {God|the Universe|whatever}, "what is my purpose," for so long, only to realize I am actually being asked that question and the asker is just waiting for my response. Coming to know who you are is often a long journey, perhaps never-ending, depending on your definition of finished. However, answers to who I am have brought me peace from mind, the mind being all I was trying to appease by some new toy theory to juggle, programming language to learn, or other distraction to concentrate on.

Where you are going, as a question, is, "what is your current goal?" If you have this agitation that your goals are distractions or are perhaps meaningless, also ask yourself, "why," regarding what your current goal is. Iterate on that until you've found something meaningful and satisfying to you and then go with it. Where you are going will naturally change over time, sometimes multiple times a year, sometimes once every 5 or 10 years, unless you are the rare type who pursues a lifelong mission that outlives you. But even then, you will likely have milestones along the way.

When we know who we are and where we are going, we can return to the deluge of information, but this time with a natural filter. We're here with a direction and a purpose. We take what is useful, we're thankful for all else but are not distracted by it or {time|compute}-enslaved to it. It's worth noting, it's useful to allow ourselves time to play and wander periodically (the search part of search-exploit, if you will). It's not about always filtering but rather about having the filter and the awareness to apply it as necessary.

The fact that you are already looking means that it is only a matter of time, so travel with a peaceful mind, fellow sailor!

Given what I understand about you so far, if you have not already read The Beginning of Infinity (David Deutsch), please do so if you're looking for any bootstrapping.

Aside:

"You program long enough and the patterns emerge, and you start to see things."

I hadn't heard of the Gang of 4 book until years into my software engineering career. When I read it, everything in the book I actually cared about was already familiar. I had developed it myself via the Feynman Algorithm. And I don't say this boastfully--I'm no genius. I just had problems and thought hard about how to solve them well until I solved them. One amusing thing I noticed, was that because I had derived the designs myself in-context, it stood out to me immediately when a peer appealed to the Gang of 4 in a, "well, I don't know, but these guys say..." way. Which is not The Way (tm).

Godspeed.

Here's the curated commit log for last week.

2025-12-03

fix: allow player to change facing direction even if they can't move

2025-12-03

refactor: wrap platform-side details (renderer, screen dims) in struct

2025-12-03

feat: use renderer logical presentation to support arbitrary upscaling

This also removes explicit transformation from world tiles to world

pixels as world pixels were only ever used as an intermediate frame when

transforming to screen pixels.

2025-12-04

docs: add concept groundwork for first game; separate next game content

2025-12-04

feat: add first enemy, random movement; add entity-entity collision

2025-12-05

fix: round lowest visible tile idx toward 0 to fix gap in map_render

I split my time three ways this week, one by necessity and another mostly by chance. As this post is about solo game dev, I will share details peripheral to development from time to time as they are part of the journey. In this case, the by-necessity thing was applying for health insurance as it is mandatory to have if living in Japan. I'll split that into another short post, though.

The second thing was game design. While I will go into detail about the mechanics and perhaps level design, I will probably never go into much detail about the story itself, as I'd like to leave that up to players to experience and interpret. I guess I can elaborate a bit on my trajectory until recently, though. I plan on this being my first game I'll publish and sell. I'd love for it to be "successful," but I don't bank on that at all, pun intended. What I want to do is get experience going end-to-end, from an empty file in a text editor to a game in the market. That will be quite a journey, but that will be the first iteration. From there I'll learn whatever I can and repeat. Toward that, I don't want to develop slop, will try to come up with something creative and worthwhile for me and others.

At first I had an idea to clone an existing, small game I enjoyed and add some extensions. This gave me well-scoped goals and removed a big task, which was novel game design. This was all toward getting some iteration out in public quickly. Lots of the big indie game hits took 5+ years to develop. I'd like to get something out in 1 or 2 years, again, without the aspiration that my title would mean anything to anyone but me. To date, I've been developing my own game for something to the tune of 7 weeks or so, and already, my own game design ideas are popping up in my mind. I did rack my brain for the first two weeks for some interesting, novel idea I could build a game around, but nothing really surfaced. I recalled a talk I watched from Jon Blow, I think it was his keynote at GDC 2014, where he was discussing where to find inspiration for interesting games. I've also learned from my beloved Kojima Hideo-san and also Sakurai Masahiro-san. The thing I always walked away with, though, is that I'm not going to sit and try to come up with an idea that makes for an interesting story or game. And indeed, this has proven true in my life. Perhaps ironically, it is by not trying that I have had my most promising ideas for games. This time around has been no different. As I develop and think about which feature to try and implement next, ideas seem to naturally bubble up into my mind. "Ah, what if instead of the game working in this way, it works in that way?" And "that" way turns out to have some parallel with a transformative experience I had in life, and suddenly a game feature becomes a metaphor for a realization I had or a way of thinking that changed my life. And then a game feature and a story element naturally weave themselves together. I'm being vague here still so as to not spoil anything about the story I'm thinking of writing, but I think I've described the gist.

Paraphrasing the Tao Te Ching, by not doing, it is done.

I also read and listened to talks about creating game design documents. Creating one before doing any other work probably works well for the niche of people that are borderline clairvoyants, but they don't work like that for me. In fact, they smell like the stereotypical project manager who tries to outline a product on paper and get it right the first time. Of course, the game design document is a living document in either case, so it does evolve over time, typically to be come less prescriptive and more descriptive. For me, the way it works is that I develop something, seem to naturally get interesting ideas over time related to my life experiences, and then I just jot the ideas down in a Markdown file checked in at the root of my game's repo. It's less a design document and more a journal of the concepts at play in the game and ideas I've had that I want to explore further. Once I have such ideas, these are seeds from which I can sit and intentionally think more deeply about and further develop. Going from 0 to 1 idea-wise, I have no process for. I often just need to let my mind wander (/wonder). Once I have 1, I can play with that intentionally and grow it in this and that way.

One guiding principle of my game design is that I want to respect the player's time. What I mean by this is try to share an interesting mechanic, idea, or thought with the player in 3-5 hours. The game would need to be priced accordingly, but otherwise, I don't like the thought of me creating something that, if a hit, consumes 80+ hours of tens of thousands if not millions of people's time just distracting them from something else in life.

Finally, the third thing was typical feature development. The most interesting topics this week are rendering logical presentation and adding the first test enemy.

Regarding logical presentation, after creating a 16x16 px sprite and then

rendering it in my game, I thought the sprite was a bit too small on my monitor.

I had two choices. The first was redraw the sprite, and eventually every asset,

at a larger resolution. The second was to upscale the sprite. The first would

cause the art to take more time, and the second seemed more practical, so I

tried to do the second. When I did that, I got some strange effects. There

seemed to be some sort of visual tearing between tiles. What was in fact

happening was that SDL was applying blending upon upscaling. This is controlled

per-texture using

SDL_SetTextureScaleMode.

SDL3 conveniently provides SDL_SCALEMODE_PIXELART as a scale mode, perfect

for my use cases.

Here is what rendering looked like before applying.

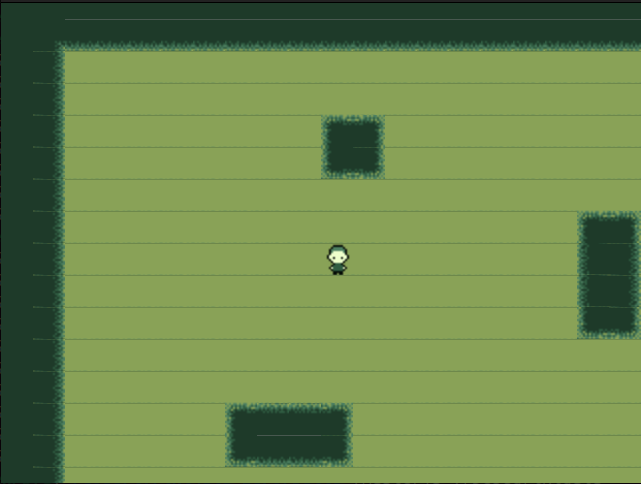

Here is what it looked like after.

![]()

You can see the "tearing" issue is fixed. The pixelart version is much sharper, although there is a nice CRT-like aesthetic to the previous scale mode, which I think was just nearest-neighbor. I'm going to keep the pixelart scale mode for a variety of reasons. I won't get into that more this time, though.

You may also have noticed that the image of the game seems zoomed in compared to images or videos in previous posts. At first, I was scaling the rendering by adding an explicit scale factor (2x) and then propagating that scale factor to all code that dealt with transforming to or working in screen pixel space. One question that naturally comes up is, how do I render to a screen space that has an aspect ratio different than my world map? If I create a scale factor based on the latest window dimensions, I will need a horizontal and vertical scale factor. Or, I could create a uniform scale factor, but what do I do when my scaling doesn't fill the entire screen in some dimension? I'd generally accommodate this manually. One would typically fill the gap with letterboxes. (Grokipedia isn't so great at the time of this writing in that it doesn't show images, and an image would explain this concept immediately. Anyway, here's to hoping the article is better in the future.)

I found that SDL has a function to handle this for me, called

SDL_SetRenderLogicalPresentation.

So I employed that function. The gist is that you have some actual screen

dimensions that the rendered image is displayed in, but you can configure a

logical render space that you will target your code/math to. SDL will handle

scaling your logical render space to the physical render space at presentation

time. So, you don't have to worry about handling letterboxing or uniform

scaling anymore. To boot, you also don't have to propagate manual scaling

factors throughout your code. Instead, I just propagate the logical render

dimensions. When I want to scale up, I configure the logical render dimensions

to be smaller than the physical render dimensions.

The second notable feature was adding my first test enemy. I hacked the enemy

directly into the game state object for now, but I realized I'll have to do

some thinking on how to efficiently manage multiple enemies (generalized to

entities) for some level or game state. Problems include: reusing an entity

asset across multiple entities instead of each entity owning its own

(potentially duplicate) asset, creating a statically-sized collection for

entities and marking some as existent/non-existent or having the collection

by dynamically-sized (so non-existence is handled via delete or remove

or something like that on the collection), and how to store information about

how many entities and their kinds to spawn and where for each level.

Then I also need to implement pathfinding for enemies.

Currently I have a simple ghost-like sprite spawned at a hard-coded location that maybe moves in some random direction when the player moves. As the game is tile-based, collision detection is simply

- check for collision on the map

- check for collision with other entity

Here is the curated commit log and post for this week's game development.

2025-11-24

chore: move standard-library-like code to src/sl ("standard library")

2025-11-24

feat: path_concat now maybe adds separators; add test and README

2025-11-24

feat: add string view path_concat overload; extend test

2025-11-25

feat: add arena allocator to standard library

2025-11-25

feat: map loading and path_concat now use an arena

2025-11-25

feat: add arena_realloc and test in preparation for using stb_image

2025-11-25

feat: introduce stb_image as library; use our own allocators; load PNGs

2025-11-26

feat: replace STBI with SDL_image; load map tilesets as texture atlases

2025-11-26

feat: render actual game map instead of placeholder game map

2025-11-27

feat: move game logic out of main; introduce persist, temp, map arenas

2025-11-28

feat: generalize aseprite_to_map tool to aseprite_asset_exporter

2025-11-28

refactor: extract map into general tileset asset

2025-11-28

feat: load player sprite, add player-facing direction

Last week's commit log query started from the beginning of time in my repo, so

I've added a new filter to the git log query, --since. Again, mostly just

pasting this here for my reference.

git log --pretty=format:"%ad%n%B" --date=short --since "2025-11-24" --reverse

As the first commit suggests, I've extracted some features from my game into a

separate library I'm calling sl, just meaning "standard library." It's

essentially a variety of game-independent utilities that I would typically find

in a languages' standard library but flavored to my taste.

path_concat, which I posted about in last week's post, will now add path

separators when required. This change is ultimately what led me to introduce

arena allocators which I did shortly after. Without arena allocators, the caller

has to set up enough buffer space for the string concatenation, and the

requirements to set up the buffer correctly grew as the function became more

featureful. Some months ago, in my last group of posts about the game I am

making, I discussed arenas, so I won't be going into them here.

At the beginning of the week, I was rendering a placeholder map and character. I already had Aseprite map loading working in my game last week, but I was not rendering the map. This week I tossed out the placeholder map and am now rendering "real" maps. This made testing a lot more fun. It also reminded me that I need to get a lot better at pixel art :) Anyway, the idea was just to get something rendered to test the end-to-end art-to-play path.

I previously implemented collision by just checking the tile ID of the tile the player wanted to move onto. Now, as I probably posted about months ago as well, I export at least 2 layers from a single map in Aseprite. The first is the layer containing the graphics for the map, essentially the painted tiles. The second is the collision layer. I use a single tile, typically red, in the collision layer to indicate which spaces have collision. Collision in this case means things like walls. For interactable things in the map, this will likely be a third layer (or maybe an extension of the collision layer) which indicates the spawn locations of various entities. I'll then create the entities at runtime and they will particpate in the dynamic game update loop, not just be static in the map. This is how you can have opening doors, switches, things like that.

Actually, about arenas, one new thing I did with mine is implement the realloc

behavior described in

malloc(3). This was

because I was preparing to use STB image to load tileset PNGs from Aseprite, and

I didn't want to implement a PNG parser myself. STB image kindly provides

STBI_REALLOC_SIZED

which is like realloc but passes the size of the existing allocation for use

in allocators that don't track individual allocation size. This is often the

case for arena allocators, and mine is no different. As you can see in the

commit log, I forgot and then later remembered that SDL provides SDL Image to

do the same thing. Since I'm already using SDL, I STB image and use SDL Image

instead.

I also moved all of the game logic out of main.cc into its own game.{h|cc}

file. This is to help separate the OS-specific platform portion of the

implementation from the OS-agnostic game logic. I will have to add OS awareness

to things like my standard library, but that will come later. As part of moving

the game logic out of main.cc, I also created a few arenas on the platform

side, bundled them up into a simple Memory struct, and hand them off to

game_update which is the entrypoint for my game logic for a single frame.

Lastly, I also replaced rendering of the placeholder character with rendering

of one I drew in Aseprite. I drew 4 sprites for the player: up, down, left,

and right. I could have just exported a sprite sheet (as PNG) and loaded that

into an SDL_Texture, but since I already have an Aseprite-to-binary workflow

with the aforementioned conversion tool, I create the player as a tilemap,

export that, and then re-use my binary-parsing logic to get at the tileset for

the player. Thankfully this doesn't waste any memory ultimately. I allocate

the tilemap in the temp arena and just copy out what I need into the persistent

arena. The temp arena gets cleared at the end of the current frame on the

platform side.

There is a bit of a catch, though. Here is a cobbled-together group of struct definitions from across various game files.

struct Tileset {

SDL_Texture* atlas;

size_t atlas_width_tiles;

size_t atlas_height_tiles;

uint16_t tile_width_px;

uint16_t tile_height_px;

};

struct Entity {

EntityType type;

Vector2f pos;

Tileset ts;

};

struct Player {

Entity e;

FacingDirection facing;

Cooldown move_cooldown;

};

struct GameState {

uint64_t perf_frequency;

const char* base_path;

Player player;

Camera camera;

Map map;

};

Starting from the bottom of the definitions, GameState is what lives in my

persistent arena. Persistent means the memory survives across frames.

A Player is an Entity by composition, and an Entity contains a Tileset

which in turn contains an SDL_Texture. I have not replaced SDL's allocators

with my own allocators, and I'm not sure if I will. This means that I let SDL

use whatever its backing allocators are (not necessarily malloc), but I don't

control the memory pool itself. So, things are a little bit fragmented across

memory--I control many allocations in my game logic, but SDL just does whatever

it wants.

The reason I have not replaced SDL's allocators is because SDL uses free quite

a lot. I think I might have posted about this before... Anyway, I don't want to

write an optimized allocator at this time in my life. When I implemented "free"

for STB image, it was just ((void)0), meaning that I didn't actually do

anything, because my arena can't free individual allocations.

We'll see if this hurts me down the road.

Anyway, last point for today, about the Tileset. The name of the texture is

atlas. An atlas is just a single texture that may contain multiple tiles.

You get at the tile you want by specifying a subset of the atlas as a

source rectangle

when rendering. Player::FacingDirection in my case doubles as an index into

the atlas, so when I render a player, I render one of the aforementioned

directional sprites by indexing into the atlas.

In my last implementation, I was loading a unique texture for every sprite.

That may be less efficient at render time if the allocations for the sprites

live far away from each other in memory. That, and it's just more things to

keep track of. Map also uses Tileset, so atlases benefit us there, too,

where there are many more sprites than there typically are for entities like

players.

Here's a demo. Pardon the programmer art.

The year is 750 AD. It's central Japan, the Nara Period, the tail end of winter. The cold is biting.

It's early in the morning. The sun has just started to peak over the mountains and through the trees. You're outside, wrapped in multiple layers, shivering. But you don't think about the cold. There are tens of other people around you doing the same. Everyone is facing a single person standing before everyone else. Let's call him the foreman. The foreman is giving out the instructions for the day. People will split into teams and go here and there. Everyone's general task is to cut down trees and prepare planks from them for carpenters to further refine.

You pick up your tools, hands hardened from all the work you've done up until now. You move with your team to your designated area. You self-organize into smaller units, some working in tandem to cut trees, others cutting fallen trees into logs, stripping bark and branches off of them. You get stuck in the group that has to chop the trees down. You and your partners gather around various trees with axes, each chopping away. You had an idea to create a long sawblade that two people could hold, one on each end, and you could fell trees faster with less work individually. It'll have to wait, though, as you can't create that on the spot. You wished you were in the team stripping logs or hauling them back to camp. Chopping down trees is hard work, and your team is the bottleneck. The others are resting while waiting for another tree to log and haul.

As you work, your body heats up, and you start to sweat. You remove a layer. It's uncomfortable, and you can smell the odor of your teammates as well. But these trees aren't going to fell themselves, and you can't let everyone else down. You try not to think about tomorrow, but you know you'll be back to do the same thing all over again. At least you'll get to rotate to a different responsibility.

6 months pass. You haven't always been felling trees for this time, but you've been doing similar manual labor otherwise. You think about the nobles who have come through town while you work. Ah, to be like them and not have to work so hard. Whatever, どうでも良い.

It's the middle of summer now, and its sweltering hot. You sit on cool stone in the middle of the day, unlike your days prior toiling away when it was colder. You're shaded from the midday sun by a large wooden overhang that is just one part of a large castle-temple complex. Last year this overhang wasn't here, and everyone felt its lack literally. You remember getting caught in the summer rain brought by the typhoons. It wasn't even refreshing. The air was so humid, and the rain was somehow warm. You were hot and miserable, and everyone smelled.

But this year is different. You sit under a tangible structure protecting you from the elements. Many others do the same. You weren't the carpenter, you weren't the architect, you aren't a noble, but everyone knows that you pitched in and is thankful for that. It starts to rain. You and your buddies look out into the damp heat and then look at each other, smile, and give a sigh of relief.

Summer transitions into fall. It's cooler now, and you're back to work, moving large stones from a quarry to a mason's workshop. The mason does his thing, and then you move shaped stones elsewhere around the castle-temple complex. It's monotonous drudgery. You wish you could be out helping your parents plant or pick rice like you did when you were 8 years old, daydreaming about goofing off with your friends later on or listening to some bizarre stories and wondering about the world. Whatever, どうでも良い. These stones aren't going to move themselves.

The next winter comes, and the cold is once again biting. The town doesn't need as much wood this time around, so you've moved on to other tasks, doing grunt work on farms, for smiths, for masons. This year the cold is more pronounced, though, since you have something to compare it to. You and your buddies look out into the snow falling around you, recalling simultaneously freezing and sweating this time last year. You're a little too hot, so you lift yourself out of the onsen, and steam billows from your body like you're some sort of deity. You feel like one, at least, knowing that the blood and sweat you put into all that work with wood and stone has provided for everyone around you, and everyone else knows it too. You built something that has measurably improved your own life and the lives of people around you, and you presumably get to enjoy it for the rest of your days.

The year is 2025 AD. It's Tokyo, the Reiwa Period, the tail end of winter. The cold is biting.

It's early in the morning. The sun has just started to peak over the mountains and through the trees. You're outside, wrapped in multiple layers, shivering. You think about the cold. There are tens of other people around you doing the same. Everyone is facing a single person standing before everyone else. Let's call it the crossing signal. The signal is giving out the instructions for when to walk. At work, people are split into teams. Everyone's general task is to move information from one service the company pays for to another service the company pays for.

You unlock your computer, heart hardened from all the work you've done up until now. You check-in with your team on your designated Slack channel. You self-organize into smaller units, some working in tandem to address this problem, others essentially creating new problems. You get stuck in the group that has to fix problems. You and your partners gather around various documents, each cross-checking, debugging. You had an idea to create an automated test barrage, so you could catch issues earlier, faster, with less work individually. It'll have to wait, though, as you can't create that on the spot. Thankfully they run the heater late into the night, so you can stay late and develop it on your own time. You wished you were in the team creating new problems for everyone else. At least they get to create puzzles for themselves and then code up solutions. Fixing problems is hard work, and your team is the bottleneck. Management is waiting for another fix to send to the customer.

As you work, your body heats up, and you start to sweat. You remove a layer. It's uncomfortable, and you can smell the odor of your teammates as well. But these tasks aren't going to finish themselves, and you can't let everyone else down. You try not to think about tomorrow, but you know you'll be back to do the same thing all over again. At least next quarter you'll get to rotate to a different responsibility.

6 months pass. You haven't always been fixing problems for this time, but you've been doing similar labor otherwise. You think about the managers who have come through the org while you work. Ah, to be like them and not have to work so hard. Whatever, しようがない.

It's the middle of summer now, and its sweltering hot. You sit in a climate-controlled office in the middle of the day, just like your days prior toiling away when it was colder. You're shaded from the midday sun by a large, sterile ceiling that's just one part of your company's massive office. Last year this ceiling was there, and you didn't even think about it. You were caught in the summer rain brought by the typhoons on your way in. It wasn't even refreshing. The air was so humid, and the rain was somehow warm. You were hot and miserable, and everyone smelled.

This year is no different. You sit under a tangible structure protecting you from the elements. Many others do the same. You weren't the carpenter, you weren't the architect, you aren't a manager, and you didn't pitch in. No one even takes a moment to be thankful for the structure. It starts to rain. You and your buddies don't even look out into the damp heat, are fixated on meeting deadlines for people they don't care about, building something they'll never use, for people that will never know them, if the product isn't scrapped on the whim of someone entirely disconnected from the work.

Summer transitions into fall. It's cooler now, and you're on a different project. The teams around you do their thing, and then you integrate it. It's monotonous drudgery. You wish you could be out helping your parents garden like you did when you were 8 years old, daydreaming about goofing off with your friends later on or playing some fantasy RPG and wondering about that world. Whatever, どうでも良い. These tasks aren't going to complete themselves.

The next winter comes, and the cold is once again biting. Your org didn't need as many people this time around, so you've moved on to other tasks, doing grunt work for the next project. This year the cold is no more pronounced. You look out the window into the snow falling, recalling nothing. You're a little too hot so you take your jacket off. Steam billows from your coffee like some sort of demon. It feels like one, at least, knowing that you depend on it to keep you going, pouring sweat and life into all that thankless work you have to do. Everyone knows it, so you tell yourself its okay, but they don't care, because that's just life, isn't it? You built something that has measurably improved nothing, and you don't even get to enjoy it, because you never really needed it anyway. And you never will for the rest of your days.

I had joined a startup a few months back, but I recently left. Back to my own thing at this time in my life.

When I first left industry to do my own thing, so many people asked me what was next for me and were surprised by "doing my own thing" that I had to refine my answer to make the inevitable same-conversation-many-times efficient. The common question to me was, "what would it take for me to work for someone else again?"

My answer was, simply needing money aside, three criteria.

- The company is a small group of experts.

- The group has a single, measurable mission.

- The mission and tasks resonate with me.

I've since added a fourth criteria: everyone is humble.

Also, I've created a new rule for myself for any interview I participate in from here on out. That rule is, if I want to join a company, I need to first come up with my own plan and explanation of how I would accomplish their mission, end-to-end, meaning from hiring people and starting with an empty text file in front of me as a software engineer, to shipping and maintenance. It's most important to run this by company leaders to get a sense for their familiarity and experience in the domain and also to get an early read on points I might disagree with or things I might be wrong about and expectations I need to adjust.

With that out of the way, here is my next development update. I was previously writing development logs mostly daily, but now I think I will do so weekly, unless there is some singular topic I want to on about at length. It's Monday already, but I'll be posting about last week. Also, it's a three-day weekend here in Japan, but when you work for yourself and have no income yet, there is no such thing.

I'll experiment with posting a slim log and then touching on this and that. The command I'm using to print the log is

git log --pretty=format:"%ad%n%B" --date=short --reverse

2025-11-15

docs: initial commit

2025-11-15

feat: open a window, attempt FPS target

2025-11-17

feat: render a simple map the size of the window; add build docs

2025-11-17

feat: introduce create/destroy entity function; create player

2025-11-17

feat: implement basic movement and collision

2025-11-18

tweak: double running speed in tiles per second

2025-11-18

feat: introduce GameMap struct

2025-11-19

feat: add camera that follows player; also add clip rect on main window

This fixes a rendering slowdown caused by extending the map size in an

earlier commit and rendering the entire map--even portions out of the

frustum--on each frame.

2025-11-19

docs: index documentation and add docs on coordinate systems in use

2025-11-20

chore: switch tile size to 16 pixels to anticipate maps; extend docs

2025-11-21

feat: add small paths and strings library

2025-11-21

feat: add aseprite to binary map conversion wrapper tool

2025-11-21

feat: add a map parser; this commit does not include assets/, data/

2025-11-21

feat: add string view and parent path utilities

I restarted the codebase. I did this mostly to refamiliarize myself with what will become the entire implementation. I'm still using SDL3 and, by consequence, CMake. I considered switching to Jai or Odin but stuck with my favorite dialect of "C++," which is C with operator and function overloading. Aside, this podcast had some hilarious parts, where the host was hoping for hot debate around what C could do better and where it shines, didn't get it, and was getting jokingly visibly frustrated when the guests mostly kept agreeing with each other about how bad C was and why they nonetheless stick to most of its core principles.

Currently the game is entirely tile-based with tile-based positions and movement. Entities are just a struct of a position and sprite, in that order. Collision is a simple can-move-to-world-tile check at this time.

I had never implemented a camera before, so that was interesting. Being real with you, it took me an embarassingly long amount of time to conceptualize the transformation in my head. My understanding is that there are two common types of camera setups in top-down 2D games, and they differ in how the camera position is tracked. One setup tracks the camera position in screen pixels as the top-left corner of the screen (if your render system places (0, 0) at the top-left of the screen. The other setup tracks the camera position in screen pixels as the center of the screen. In my case, I track it at the center of the screen. This is so that if I want to "watch" any particular tile or entity, all I need to do is set the camera to that entity's position. Currently I do so for the player, so the camera tracks the player as the player moves.

Regarding the transformation, consider the following scenario:

+-------+(0,0) px

|

v Screen

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

X | X

X------------------ screen width ---------------------------X

X | X Game Map

X | +----------------------------------X----------------+

X | | X |

X | | X |

X | | o X |

X | | ^ X |

X | | | X |

X | screen | +---+tile to X |

X | height | o render on X |

X | | ^ screen X |

X | | | X |

X | | +---+camera pos X |

X | | X |

X | | X |

X | | X |

X | | X |

X | | X |

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX |

| |

| |

| |

| |

+---------------------------------------------------+

Assume we want to render the point labeled "tile to render on screen." To do this, we need to find that tile's position in screen space. The tile has a position in game-map tile space (Px, Py). The camera has a special property of having a position known in two frames. It has a game-map position (Cx, Cy), and we also know it has a fixed position in screen space in the center, which is (screen width / 2, screen height / 2). The formula to transform the tile to render from game-map space it screen space (Psx, Psy) is thus

(Psx, Psy) = ((Px, Py) - (Cx, Cy)) * (tile width px, tile height px) +

(screen width / 2, screen height / 2)

(Px, Py) - (Cx, Cy) gets the tile position in game map space relative to our

camera position. If the camera were at (0, 0) in game map space, the position

relative to the camera would simply be (Px, Py). Multiplying by (tile width px, tile height px) transforms the game-map tile coordinates into game-map

pixel coordinates (the coordinate now points to the upper-left corner of a

particular tile). Finally, to transform game-map pixel coordinates into screen

pixel coordinates, we need to add the camera offset. Again, if the camera were

at (0, 0), we would be done.

This transform can produce coordinates outside of the visible screen space. As one of my commit messages above suggests, if we don't avoid rendering outside of the screen space, we will pay the cost of rendering. I found with SDL3 that even if I set the render clip rectangle to the screen space, I still run over my frame times. So, I also have some logic to determine the subset of the game map to consider for drawing to the screen on a given frame, and then I apply the transform shown above to convert visible tiles to screen space.

On to game map design, I will stick with pixel art and Aseprite. I made a small

patch to my Aseprite tilemap binary exporter to adjust the exported file names,

and then I introduced a Python utility on my game-code side to transform

.aseprite files to binary map files. The script ultimately transforms as

follows:

test-map.aseprite -> .

├── test-map/

│ ├── tileset1.png

│ └── tileset2.png

└── test-map.bin

test-map.bin is what my game code parses to load in map data, and resources

corresponding to "test-map" are stored in a folder of the same name peer to the

binary file. Paths in test-map.bin are relative to the location of

test-map.bin. Avoiding absolute paths in this case is for portability,

especially since the resource location on disk in the source tree is different

than the location resources are placed after a build. I put my resources in a

data folder, map resources in data/maps in particular. To accomodate

relocation in CMake, I have

add_custom_command(TARGET the_target POST_BUILD

COMMAND ${CMAKE_COMMAND} -E copy_directory_if_different

"${CMAKE_SOURCE_DIR}/data"

"$<TARGET_FILE_DIR:the_target>/data"

)

add_custom_command(TARGET the_target POST_BUILD

COMMAND ${CMAKE_COMMAND} -E copy_directory_if_different

"${CMAKE_SOURCE_DIR}/data/maps/"

"$<TARGET_FILE_DIR:the_target>/data/maps"

)

This requires CMake 3.26. The annoying thing is that

copy_directory_if_different does not do a recursive comparison, so I need to

check the top-level data directory and data/maps directory explicitly. Also,

content removal from the source directory does not count as a difference,

meaning that previously-removed resources can linger around in the build output.

I could remove and re-copy all resources on every build, but until I hit some

gotcha, using an old resource by accident, I won't bother.

SDL3 provides a convenient

SDL_GetBasePath which allows

me to get the path the executable is run from. This allows me to then discover

my executable-relative resource directory and correctly resolve the relative

paths in the map binary files.

Something like std::filesystem would be handy here, but I'm avoid std:: as

much as I can, so I have reimplemented just what I need. Toward this, I

introduced a simple string view utility. It's trivially defined as

struct StringView {

char* str;

size_t len;

};

where the characters are ASCII-only and the len portion of the backing string

is not guaranteed to contain a null terminator. We'll see how useful this turns

out to be. I mostly introduced it because I have not introduced my scratch

allocator yet. If I had the latter, I'd allocate without thinking much about it,

knowing the memory I allocated will be reclaimed shortly after.

Toward what I need from std::filesystem, I introduced path_concat and

path_parent functions. path_parent finds the parent in a provided path.

StringView path_parent(const char* p, size_t len);

This also took me an embarassingly long amount of time to write elegantly. I won't share the code in the event you want to challenge yourself. (By the way, AI output was rather bloated and inefficient at the time of this writing.) My implementation only handles Unix path separators at this time, so this will be one implementation I need to port when going to Windows. Here are the test cases I pass, if you want to take a go at it yourself.

struct TestCase { const char* input; const char* expected; };

TestCase cases[] = {

{ "/a/b/c//", "/a/b", },

{ "/a/b//c", "/a/b" },

{ "/a//b/c", "/a//b" },

{ "/a/b/c/", "/a/b" },

{ "/a/b/c", "/a/b" },

{ "a/b/c", "a/b" },

{ "a//", "." },

{ "//", "/" },

{ "/ab", "/" },

{ "/a", "/" },

{ "./a", "." },

{ "//a", "/" },

{ "//", "/" },

{ "a", "." },

{ "/", "/" },

};

Speaking of going to Windows, one reason I'm using SDL3 is to allow myself to develop on Linux and macOS and "just" test on Windows. We'll see how that goes. I really like the idea of being able to bring my macBook wherever with me and still develop and play my game, don't really have a decent portable option with Windows at this time.

Regarding map loading and whatnot, I may ultimately bake the map data into the

final binary. I may either use the recent

#embed

or, more than likely, just implement a tool myself to achieve the same.

I heard a quote yesterday--I think it was from Chris Bumstead--along the lines of

What used to drive me now exhausts me.

I think it very succinctly captures my feelings about software development at this stage of my life.

I used to study programming for programming's sake. All you had to say was, "did you know?" and you had my attention for an entire weekend, studying more sophisitcated ways to do the same old thing, diving into arcana, reciting the new mantras. Because I liked puzzles. Because I wanted to be in the group that knew. "Did you know" is not a question anyone asks to actually learn anything. It's a lead-in to a flex. Virtue signaling. A waste of time. Studying the esoterica of physics has an end and ultimately leads to simple solutions for everyone. I find that studying the esoterica of most modern software leaves one prone to normalize and even perpetuate it.

Now the arcana exhausts me. It's mostly mental gyration, or even worse, just puzzles we have created for ourselves that get in the way of making meaningful progress for the species.

Use as few tricks as possible.

Write as little code as possible.

Add as few abstractions as possible.

Software engineering is a means to an end.

We've normalized "best practice" as a header file, an implementation file, object-oriented whatever, 5 different kinds of constructors, meta-programmed interfaces that help account for non-ref, ref, const ref, universal (lol) ref, etc. Newcomers to the field look at the awful tools and think, mastery of this is what it means to be great. The tools are so complicated that tool use itself was reified into meaningful work when no one was looking. This is why competent leadership in a company is so important--you need leaders who can discriminate between someone who knows everything about hammers and someone who knows which to reach for to build something.

If you want to transform your ego into code, that's fine, but keep both off of the critical path of something we're all supposed to use in the end. Physics doesn't care about your ego, so I'd like to keep ego out of software engineering for the species as well.

Did you know you can do pretty much everything with structs, function overloading, and operator overloading?

A Japanese person posted the following question in English on a language exchange application I use: "What makes someone feel romantic love for another person?" I've wanted to be able to discuss things like "love" in Japanese, so this seemed like a good opportunity for me to learn in context. My Japanese is still insufficient, but I'm sharing my reply here, in part because it does capture the essence I've come to understand of love, and in part to act as a benchmark of how far I've come with Japanese and how much further I still have to go.

この投稿をありがとう! 私の意見を日本語でよく説明できるかどうかわからないけど、頑張る笑

「ラブ」は人によって意味が違うね。 例えば、昔にギリシャ人はラブを三種類に別れた。 この投稿に関している「ラブ」の種類は二つがあると思う(ギリシャの分類とよく合わない)。

先ずはロマンチックなこと、つまり恋。 恋は相手の見た目、言動、地位、肉体的な相性などに関しているものだ。 恋の原因は先天的(例えば遺伝)と後天的(例えば文化、環境、社会)な要因だと思う。 このラブは二人がいて、私と私の相手だね。 カップルは関係のために取引している。 私は何かをあげる、例えば親切な言葉や時間や思いやりな贈り物や恋愛だ。 相手も適当なことをくれる。 もちろん、いい関係にはこの取引が仕事のようなことじゃなくて、カップルは互いにこうしたいから自然なことだね。 でも結局二人、私と私の相手、がいる。

一方、愛ということもあるね。 これは一体感を探すことだ。 愛の原因は、なんとか相手の中に自分自身を見ることだ。 恋の二人より、愛は一人だけがいて、「私たち」だ。 相手にちゃんと自分自身を見るために、自分自身をよくわかって愛することが必要だと思う。 もちろん相手は自分の興味や目標があるけど、相手の中に自分自身を見るから自然に心の底から応援できるようになる、もう自分のことを愛しているのおかげで。 これは愛の逆説でしょう、相手を愛するようになるために、先ずは自分のことを愛しなくちゃいけない。 自分のことを愛するために、先ずは自分のことをわからなくちゃいけない。 自分をわかるというのは、自分の目標や価値観や前のトラウマを解けることなどだ。

恋の始まりは外に見ることによる。 愛の始まりは中に見ることによる。 恋の方がわかりやすい、映画や曲やソーシャルメディアでイメージが多いから。 愛をわかるの方が難しい、あまり誰にも自分の心の底を見えないから。 (例えば両親の方が他の人より自分の子供の心をわかりやすいと思う。) もちろん、人は年に取るにつれて変える、でも愛の原因のおかげで、カップルが一緒に変えることもできると思う。

私にとって、いい関係をできるために、恋と愛とどっちも必要だと思う。 英語ではこのラブの種類について説明しかたもちろんあるけど、あまり特別の言葉じゃない(日本語とかギリシャ語より)。 私の返信のために新し言葉と表現をならなくちゃいけなかったから、もし日本語の言葉のニュアンスを誤解したなら、すみませんね! ここまで読んでくれてありがとうございます! またおもしろう投稿もありがとう!

Posted after realizing I left out another thing I wanted to share:

ところで、いい関係の基準について意見をシェアしたいと思っている。 関係は履歴証で並んでいる項目のようなことに基けば基づくほど、不安定になるの可能性が高いと思う。 給料、仕事、趣味、実績、どんな学校など、これに興味があるのは問題ない。 でもこんなものは相手の性格じゃなくて、相手の性格の結果でしょう。 私にとって、適当な基準は相手と一緒にいる時心地いいや相手を深く信じられる、ユーモアが好きや相手の親切さか思いやりが好きなど。 こんなことの方が説明するのは難しいけど、恋より人生のどの時期においてもより安定していると思う。 それにしても、恋も大事なものでしょう。

Since I last wrote, I extended the bump allocator from

last time to also provide storage persistent across

frames. This is necessary to contain at least two things: the general game state

struct and tilemap indices. Both of these need to persist across frames.

Previously, I was instantiating the game state on the platform side and passing

a pointer to it into my game-update function. The platform is otherwise

game-state-agnostic, though, so this didn't make much sense. For the tilemap

indices, I was just malloc'ing space for them. My recent goal was to remove

all instances of malloc from the game logic-side code.

Now, the allocator type definition looks like this:

struct Allocator {

void* base_temp = nullptr;

size_t size_temp = 0;

size_t used_temp = 0;

// Implementation detail: `base_persist` shall point to the beginning of the

// allocated memory.

void* base_persist = nullptr;

size_t size_persist = 0;

size_t used_persist = 0;

};

The implementation detail is because I allocate a single region of memory for

both types of storage. The temporary storage starts size_persist bytes after

base_persist. I also modified the API to separate allocations to temporary

storage and persistent storage and to only provide the reset ability on

temporary storage. Besides resetting, there is still no general ability to

free allocated memory, meaning that allocations in persistent storage are

expected to live for the lifetime of the program runtime.

The platform side sets up the allocator and its memory and passes it to my game update function. Perhaps a bit dirty, but although I am dealing with an allocator, it really is my game's memory pool with functions to manage the memory. Recall from the previous post that I do use the temporary storage a bit on the platform side to build a couple strings. This is no problem since no one should rely on exact positions of anything in temporary storage.

On the other hand, I require that the platform never allocate from persistent storage the game will use. This way, my game can always assume its game state object lives at the beginning of persistent storage. At the beginning of each pass through my game update function, I get at the game state via:

GameState* gs = (GameState*)allocator->base_persist;

My game state object has an initialized flag that tells me whether I need

to actually set it up or not. Because I use mmap to allocate the backing

storage, the storage is guaranteed to be zeroed after allocation. As a sanity

check, I make sure that if the game state is unintialized that

allocator->used_persist is also 0. I then stash pointers to this and

that in persistent storage in my game state instance, and from there I can

navigate the game memory across frames.

When initializing a tilemap, I previously dynamically allocated space for as many tilesets and layers as I needed based on what I discovered in my binary-encoded tilemap. Now, I set up storage for some fixed number of these things in persistent storage and point a tilemap instance at these persistent resources during tilemap initialization. This way I can avoid dynamic allocation entirely in the game logic, at the expense of allocating more memory up front than I may ultimately need. I can tune the allocations as the game matures.

Right now my game update function interface looks like this:

/**

* Update the game state based on input.

*

* @param a The allocator containing the memory for the game. The game requires

* that the provider does not modify permanent storage in any way.

* @param input The input to use to update the game state, assumed to be input

* toward the next frame to render.

* @param renderer The rendering destination for all graphics updates.

*/

void game_update(Allocator* a, Buttons* input, SDL_Renderer* renderer);

At first I thought it would be nice to keep SDL things out of the game logic code, but SDL itself is supposed to be my operating system abstraction, so I'm fine bringing it into the game logic code. I do call SDL routines that (de)allocate, for example creating or destroying textures. To avoid this, I would need to build a graphics abstraction on the game logic side, probably via various memory buffers allocated on the platform side and passed to the game update function, have the game code write into those buffers, and then have the platform side move content from those buffers into SDL resources. But that is just abstraction on top of the thing I'm using for abstraction, which is not the way to go.

As an unintentional follow-up to yesterday's post, I ended up writing a simple bump allocator. The motivation was that I wanted to build a routine to convert relative paths to absolute paths. For this, I need a place to store the absolute path. The relative paths are relative to the folder the game binary sits in, so I can't predict the full string length of the absolute path, meaning I need to dynamically allocate.

Here is the API for the bump allocator; no surprises if you've seen one before.

struct Allocator {

void* base = nullptr;

size_t size = 0;

size_t used = 0;

};

/**

* Set up an allocator. The allocator's memory is guaranteed to be zeroed.

*

* @param a A pointer to an allocator to set up; cannot be `NULL`.

* @param size The number of bytes to allocate. Must be greater than 0.

* @param addr The beginning address to allocate from. Pass `NULL` to defer base

* address selection to the operating system. Note that any other

* value greatly reduces portability.

* @return `false` if setting up the allocator failed for any reason; `true`

* otherwise.

*/

bool allocator_init(Allocator* a, size_t size, void* addr);

/**

* Allocate memory from the allocator.

*

* @param a The allocator to allocate from; cannot be `NULL`.

* @param size The number of bytes to allocate. Must be greater than 0.

* @return If successful, returns a pointer to the beginning of the allocated

* region. If unsuccessful for whatever reason, returns `NULL`.

*/

void* allocator_alloc(Allocator* a, size_t size);

/**

* Reset an allocator, meaning that its memory pool is considered entirely

* unused and the next attempt to allocate will start at the beginning of the

* backing memory pool. This does not deallocate anything from the operating

* system's perspective, but anything previously allocated in the allocator's

* memory pool should be considered invalid after calling this.

*

* @param a The allocator to reset; cannot be `NULL`.

*/

void allocator_reset(Allocator* a);

/**

* Destroy an allocator.

*

* @param a The allocator to destroy; cannot be `NULL`.

* @return `false` if destroying the allocator failed for any reason.

*/

bool allocator_destroy(Allocator* a);

I give the user the option to specify the base address of the memory pool or let the operating system pick it. In production, I'll let the operating system pick it, but in development, I'll control the base address so I can predict the general location of things in memory across program runs.

In the implementation of allocator_init, I use mmap instead of malloc,

like so:

bool allocator_init(Allocator* a, size_t size, void* addr) {

assert(a);

assert(size);

int flags = MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS;

if (addr) {

flags |= MAP_FIXED_NOREPLACE;

}

a->base = mmap(addr, size, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, flags, -1, 0);

if (!a->base) {

return false;

}

a->size = size;

a->used = 0;

return true;

}

In short, we permit reading and writing on the allocated space, the memory

region is private to our process (MAP_PRIVATE), we do not use file-backed

memory (MAP_ANONYMOUS and -1 for the file descriptor parameter), and

should the caller request a specific base address, we tell the operating

system to use a fixed address and force failure if our requested address has

already been mapped by us elsewhere in our process (MAP_FIXED_NOREPLACE).

I'm using this as a frame allocator, meaning that at the beginning of each frame

(at the beginning of each iteration through the game loop), I call

allocator_reset. I set up the allocator right after initializing SDL near the

top of main, outside of the game loop. This allows me to use the allocator

before entering the game loop for any one-off scratch work I need to do, and

then immediately upon entering the game loop (with the exception of capturing

the frame start timestamp), the allocator is immediately reset.

Before entering the game loop, I use my relative-path-to-absolute-path utility

to build the full path to the game logic library so that I can check its last

modification time via stat. I then periodically re-build the full path in the

game loop when I go to re-check the modification time, so in the future, I will

likely also introduce separate, persistent storage to cache such things.

Instead of having to implement my own way to get the base path of the game

binary across operating systems (using convenience functions in Windows and

checking /proc things in Linux, for example), I can thankfully just leverage

SDL_GetBasePath.

The interface of my routine to build absolute paths looks like this:

char* abs_path(const char* path, Allocator* a);

It takes an allocator to use to obtain storage for the final string. The Jai

language I mentioned in a previous post does something similar for routines that

need to dynamically allocate but passes the current allocator to the function

implicitly in an argument called the context. I don't have that language feature

in C/C++ without approximating via OOP, globals, or function/method partials,

so the allocator is an explicit parameter in my case. I don't like this

signature much, but it accomplishes what I need. I haven't covered this detail

yet, but I have also separated more of the game logic code from the "platform"

and exposed a higher-level game_update function from the game logic library

to the platform. The game_update function will likely eventually receive a

handle to the frame allocator so that it can allocate whatever it needs in a

single frame in a manner I can easily control and introspect. That is how

game logic code will also be able to use things like abs_path without owning

any particular allocator or backing memory pool.

Here are a couple other things I learned along the way. First, it is not only

Linux that has alloca;

Windows

has it

as well. The main difference besides the literal function name is that Linux's

causes undefined behavior on stack overflow whereas Windows's will raise a

structured exception.

I could use this for building strings as I don't anticipate memory required

for paths to be so large that it would cause a problem on the stack. The

second thing I learned is that man pages can even reference books. I noticed

the man page for mmap(2) (Linux man-pages 6.7, 2023-10-31) referenced

what appeared to be a book, and upon looking it up, indeed, it is "POSIX. 4:

Programming for the Real World," by Gallmeister. Interesting, might want to

skim through it.